The first time someone told me to try Ozempic was last Thanksgiving. I had already lost over 50lb in the preceding nine months just from making modest lifestyle adjustments, and I had solved the nascent health problems that had set off the urge to make those changes in the first place. I was still undeniably a fat person, but I was feeling incredibly proud of how I had taken some initiative and control, and gotten to a healthier place all on my own. For the first time in my entire life, I was comfortable with my body.

After you lose a significant percentage of your body mass, no matter how big you were to begin with, your metabolism slows down in an effort to conserve what’s left. Once this happens, it makes further weight loss increasingly difficult, and by Thanksgiving I had hit the plateau. So it was then, on the fattest day of the American calendar, that my relative urged me to look into the hot new miracle drug. She was taking it for her diabetes, had lost a tremendous amount of weight, and was quick to sing the drug’s praises. “Ask your doctor about it,” she urged.

I knew she meant well, but I felt a flush of shame and sadness then. I had my health, I had my self-esteem, and I was happy – but other people were still ready to take one look at me and assume that I wasn’t. And if someone who knows me can make that assumption, how many dozens of strangers must be passing a similar judgment on me every day?

I have been some degree of fat my entire life, and I most likely always will be. As a child and as a young adult, I was bullied, rejected and shamed for this in ways that have undeniably shaped who I am.

It didn’t matter what I ate, or how active I was. Even when I was a teenager at my peak physical shape – playing rugby on a team composed mostly of boys, tackling enormous guys who didn’t make the football team, and being ordered to do wind sprints by an ex-marine coach – I still wore a size 14, which in 2000s high school terms was very much an outlier.

My parents are both excellent cooks who raised me to love food, but their cooking was usually health-conscious: Honey Nut Cheerios and the occasional bag of Baked Lay’s were the most indulgent groceries they bought. I enjoyed eating my vegetables – as a toddler accompanying my mom to the grocery store, I used to hassle her to snap off a piece of raw broccoli for me to gnaw on. I drank skim milk with dinner. I went on long walks. And still, I was fat, crying in Delia’s dressing rooms and receiving well-meaning backhanded compliments from relatives about how I was “still pretty, even though …”

All this is to say I realized some time ago that I would never, ever be thin: I am simply not built that way. This realization, plus everything we already know about the pitfalls of diet culture, had made any attempt to lose weight seem both futile and like a good way to make me hate myself. So until last year, I had never even tried. My weight crept up, and up, and up. Finally, after a physical in late 2021, my blood sugar came up right on the border of the prediabetic range. It was clear: I had been playing with house money up to this point, but now, at 34, youth was no longer on my side.

With my future health in jeopardy, I became determined to make some changes – but I knew I owed it to myself to do it in a way that would not make me miserable, trigger self-hatred, or set me up for long-term failure. I had to walk a difficult tightrope: trying to change my body, while simultaneously resisting the ever-present impulse to hate the body I presently had.

At times, this felt virtually impossible. In the early weeks, I even tweeted: “Dieting is not so much about losing weight as it is about gaining an eating disorder.” Thanks to significant help from my therapist, I was able to revise my dark joke into a more useful mindset: it wasn’t about losing weight, but about gaining health, strength and energy.

To my infinite surprise, it actually worked. A year later, I had lost 55lb and my blood sugar was back firmly within normal range. My cholesterol and blood pressure, which had both been running a little high, had also plummeted. I had done it: I’d managed to restore my health and lose significant weight without spiraling into self-hatred or developing disordered habits.

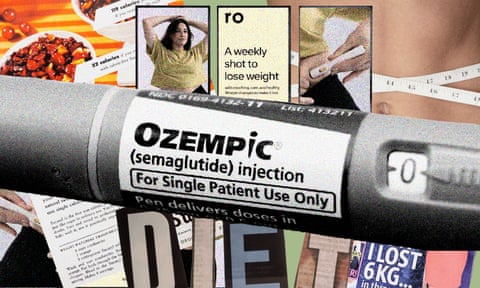

It should come as no surprise, then, that I find the explosive entrance of Ozempic into the cultural mainstream galling. The breathless articles, the Oscars jokes, the TikToks: they’re all about how already healthy people are using a new injectable drug to whittle themselves down, pursuing thinness at any financial or physical cost, because being fat is the worst kind of failure.

For a while, it seemed the cultural conversation about size and fatness was limping along some sort of vaguely progressive track. It was far from perfect (it mostly just amounted to “Check it out, there are fat models now”) but it felt like something. The tone of the discourse around dieting and weight loss had shifted, and there was a growing attitude on social media of self-acceptance. People of all demographics were pushing back against fatphobia, nutritionists and food-world influencers were emphasizing balance over restriction, and there seemed to be a general rejection of the poisonous narratives around food and appearance that most of us were raised with.

I liked it because I am soft-hearted and always rooting for people to be kinder to themselves. But I also liked it because as a fat person, it was nice to feel less openly despised.

In retrospect, it was painfully naive of me to buy into any of it. The present-day body positivity movement is a watered-down version of an older and more radical fat activist movement, its ideas repackaged for mass consumption by advertisers and marketers. It does not ask us to work on how we regard and treat others, it only asks us to feel better about ourselves. It is purely self-love, with an emphasis on the “self”: the ultimate exercise in navel-gazing.

The goal of this form of “body positivity” is still to have you find yourself lacking, to get you to want, to get you to buy – and whether the capitalist powers that be are using Kendall Jenner’s body or Lizzo’s confidence to sell you your shapewear doesn’t really matter.

But there’s one thought I keep coming back to: any activism that does not require you to engage with how you treat your community is not activism at all, and any social progress that is being pushed mostly by market-driven forces has the ability to simply, one day, disappear.

That disappearance is more keenly felt now that the “oh-oh-Ozempic” jingle is coming out of our television sets at an alarming rate, but it began a while ago, perhaps with last year’s breathless headlines that asked us “could thin be in again?” Most of those pieces took an appropriately dismissive and critical stance on the resurgence of thinness-as-aspiration, but it wasn’t enough to keep the anxiety at bay. Women all over the internet expressed displeasure, as the changing whims of advertising agencies seemed poised to disrupt the newfound positive relationships they had with their bodies.

Not enough of us read those headlines and bothered to ask ourselves the real question: why are bodies, something we are all born with and have limited control over, being subjected to the same trend-focused language as a haircut or a pair of shoes?

The Ozempic moment neatly lays bare exactly how much our society still hates fatness and fat people, and the extreme measures people who are already physically healthy are willing to put themselves through to be just that much leaner. The powers that be have decided they are bored of paying their desultory lip service to the fatties, and apparently, most of us have no problem following suit.

There’s also something deeply unsettling about how society’s “acceptance” of fatness has evolved and devolved alongside conversations about race. The foundation of fat liberation was built by Black women, and anti-fatness and anti-Blackness have historically gone hand in hand, so it’s not surprising that both communities are experiencing mirror-image ebbs and flows of public interest.

Now, with the rise of Ozempic after a brief period of so-called body positivity, there is an all-too-neat convergence taking place, where promises that were made to Black communities in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement are experiencing a large-scale corporate and cultural rollback.

Brands were quick to capitalize on a fractured cultural moment by vowing to increase their efforts at diversity and equity and by supporting Black-owned businesses. Almost three years later, that tide of enthusiasm is receding fast: take, for example, the fact that Black creators suddenly found fewer brand partnerships on offer to them during this year’s Black History Month, or the recent revelation that Spotify has used less than 10% of its $100m diversity fund.

This is a classic sleight-of-hand trick that corporations do when they’re in hot water: instead of removing the source of the problem, they promise to throw some money in the opposite direction. As soon as we look away for just a second, they stuff their promises right back up their sleeves.

We badly wanted to believe their sudden interest in us was anything other than profit-driven cynicism. How naive we were, and how deftly and insidiously capitalism can kneecap activist movements.

On that Thanksgiving Day, my brain stalled out for a minute thinking of a way to respond that would not hurt my relative’s feelings. I was truly glad Ozempic had helped her with her health, but I also wanted to make it clear I wasn’t interested in resorting to pharmaceutical intervention. “I think I would just prefer to do things without medication, if I can,” I said.

The conversation moved on, but I have been thinking a lot about that moment since then. I have been focusing just on maintaining my weight loss and healthy habits for the time being, giving my body time to adjust to its new set point and prioritizing other aspects of my life. It’s going well, but every so often the idea still worms its way into my head: “Maybe I should try it. Maybe I’d lose another 50lb …”

But the simple fact is that I would rather just stay fat than take a drug that completely rewires my most basic impulses. Ozempic is a new drug, and its long-term effects aren’t yet clear, but it is pretty much universally agreed upon that once you stop taking it, the weight will come right back.

Side-effects include vomiting, nausea and diarrhea that can get so intense you land in the ER. The fervor surrounding it has caused shortages, meaning the people with diabetes who actually need Ozempic are having a hard time procuring it. The rapid weight loss the drug facilitates causes you to lose muscle mass and can make you look older, as facial skin sags and wrinkles begin to surface.

All of this sounds unappealing enough already, but what turns me off the most is just how desperate it seems. Face the facts: when you are already healthy and a below-average size, and you go to such absurd lengths just to winnow yourself down a little, you are actively trying to put as much distance between yourself and fat people as you possibly can. What does that say to the fat people in your life? What does that say to the people like me who, no matter what they did, would still be on the heavier end of the spectrum? It tells us that a part of you is disgusted by us, that a part of you has contempt for the way we are and the way we look.

Thinness is not accessible to everyone, and it never will be – both for reasons of genetics and for reasons of economic inequality. Knowing this, we need to do the challenging work of truly accepting that bodies come in different sizes, and learning to not treat people any differently based on how they look. We need to achieve actual body positivity, instead of the banal, corporatized, self-absorbed version.

This is not to say that any effort to lose weight is cowardly or misguided, and it’s also not to say that fat people owe it to their community to stay fat. I lost weight, after all. But once I had reversed the worrying numbers on my physical and the weight stopped coming off as easily, I sat down and thought about what reasons I had for chasing further weight loss.

Being attractive to more people, having access to a wider range of clothing options, and not having to worry about being prejudged by others were the only real reasons I could come up with, and all of those reasons have everything to do with other people’s fatphobia. They have nothing to do with how I feel about myself.

And how I feel about myself is good. I like how I look, even naked. I am satisfied with what I see in the mirror. It might be hard for other people to understand that, but I feel immensely lucky to have reached a point where my health, my lifestyle and my self-image are all in places I am comfortable with. No one can take that feeling away from me.

Trust me when I say that you can learn to feel this way too, regardless of what size you are. Getting to that place might be harder than just sticking yourself with a needle, but the journey is infinitely more rewarding.