Last month angry commuters dragged two Extinction Rebellion protesters off the top of trains at a tube station in a working class, historically poor district of east London during morning rush hour. The demonstrators were trying to force the British government to take action on the climate crisis.

Their protest – which disrupted thousands of people’s journeys to work – was rapidly criticized as wrongheaded and out of touch by members of the public, across social media and in the press.

Extinction Rebellion, or XR, is a decentralized organization. Anyone can act in its name if they adhere to the group’s principles and values.

While it’s not clear who made the decision to protest at Canning Town on October 17, the negative response has helped to spark change and self-reflection within one of the world’s highest-profile environmental movements.

‘This is a rebellion’

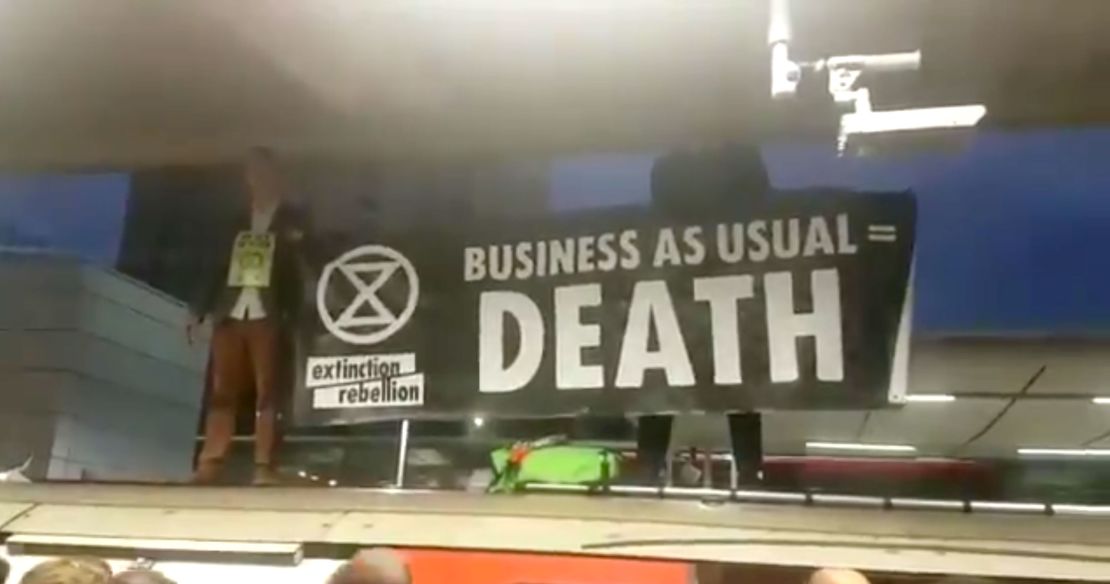

Footage of that chaotic morning in east London went viral.

“Business as usual = Death,” read the banner held up by the protesters as they towered over a platform packed with furious commuters.

“I have to get to work. I have to feed my kids!” one commuter could be heard yelling at the pair.

Cups were hurled at the campaigners, and things turned ugly: One protester was dragged to the ground by his legs and hit by angry travelers before eventually being rescued by London Underground staff and other passengers.

While the decision to target public transport in a working class, ethnically diverse area of London did give Extinction Rebellion publicity, Kofi Mawuli Klu, a senior figure within the movement, told CNN that there were “shortcomings” in the way the Canning Town protest was carried out.

Mawuli Klu, a Ghanaian-born British citizen, said such actions, “need to be preceded by working within the local community.”

“But the disruptive nature of the actions are supported by the overwhelming majority of us,” he added. “This is a rebellion and this an attempt to make people aware of the far worse lethal disruptions that are going to happen when there is societal collapse. We have no apologies to offer for the disruptions, but it is how these disruptions are organized and the lack of local community involvement, because of the gross inadequacies within XR, to doing local community work properly.”

Other senior figures within the movement have also conceded that the tactic was a mistake. “Obviously we did not get that right,” Sarah Lunnon, a member of Extinction Rebellion’s political circle, told UK newspaper the Guardian.

The protest at Canning Town – one of three London tube stations targeted at the end of two weeks of large-scale disruptions in the city – highlighted what many argue is the problem with mass environmental movements: they are too white, too middle class, and lacking in empathy for the least well-off in society.

A 2014 University of Michigan study that looked into 293 mainstream NGOs, foundations and government agencies found that the “current state of racial diversity in environmental organizations is troubling.” It concluded that the percentage of minorities employed as staff or on the boards of the organizations studied did not exceed 16%.

“Once hired in environmental organizations, ethnic minorities are concentrated in the lower ranks. As a result, ethnic minorities occupy less than 12% of the leadership positions in the environmental organizations studied,” the study added.

“It does have a race issue,” art student and Extinction Rebellion protester Annabelle van Dort told CNN. But Van Dort argues that Extinction Rebellion has at least brought the climate crisis onto the political agenda.

Privately educated in a wealthy area on the outskirts of London, Van Dort said she has long been accustomed to being the only person of color in a room. She said the Extinction Rebellion meetings she goes to are largely attended by white, middle-class people, which doesn’t bother her personally.

“I don’t feel like I can’t go because I’ve always had that my entire life,” she said, “but talking to some of my friends who aren’t white and aren’t middle class, they say it’s not for them.”

In photos: The Extinction Rebellion protests

Immediately after the Canning Town protest, longtime climate justice activist Suzanne Dhaliwal was critical of Extinction Rebellion in an opinion piece in a London newspaper.

A month later, she told CNN she feels stronger than ever that Extinction Rebellion is not representative enough.

“I don’t have another decade to raise these questions about diversity in the movement,” she said. “The fact that it’s even a question is problematic itself because it’s obvious, from the make-up of the speakers, where the resourcing is, and the fact so many people of color have been speaking against (it).”

The group seems to be responding to critics in the frequently asked questions section of its website. In response to the question, “Aren’t you just a group of middle-class left-wing activists?” the group says: “Extinction Rebellion is made up of people of all ages and backgrounds from all over the world. From under 18 to over 80 year olds – there are thousands of people willing to put their liberty on the line to fight the climate and ecological emergency and protect biodiversity and atmospheric health. … We are working to improve diversity in our movement.”

Shrinking space for direct action

On October 31, Extinction Rebellion celebrated its first birthday. From its foundations in the small English market town of Stroud, an international environmental movement has blossomed.

Extinction Rebellion’s rise over the last 12 months has been remarkable, but the climate crisis is an issue that impacts everyone. It is about society, power, race and class, so a successful mass movement must appeal to a broad spectrum of society.

On its website, the group says non-violent civil disobedience is the best way to achieve “radical change.” April’s headline-making demonstrations in London closed down bridges and streets as thousands of people poured onto the streets and hundreds were arrested. Nearly 10,000 people who had signed up with Extinction Rebellion worldwide by April said that they were willing to be arrested, according to a spokesperson. More than 80% of them also said they were “willing to go to prison” to demand action on climate change.

“You put the police in a dilemma,” one protester Nuala Gathercole Lam, told CNN in April. “If you have got thousands of people refusing to move, they either have to let you do it, which is hugely economically disruptive, or they have to arrest you.”

But its critics say that not everyone can put their liberty on the line. Following April’s protests, an open letter published by Wretched of the Earth, a grassroots environmental group which represents black, brown and indigenous people, called on Extinction Rebellion to rethink its strategy on arrests, “Many of us live with the risk of arrest and criminalization. We have to carefully weigh the costs that can be inflicted on us and our communities by a state that is driven to target those who are racialised ahead of those who are white.”

Extinction Rebellion seems to acknowledge the criticism in the FAQ section of its website, saying: “We give people information about arrest and those of us who are white have acknowledged our privilege, in the likelihood that we will be treated differently / better than our colleagues of colour. People can take a variety of roles.”

Months after the April action, as civil disobedience returned to London and spread to cities across the world, a “Thank You” note and flowers were left by an Extinction Rebellion protester for staff at Brixton police station.

For a movement that wants more voices to come into play, it was a gesture that risked alienating large portions of the community in a part of London long marked by tensions between police and the local Afro-Caribbean community.

Dhaliwal argues that Extinction Rebellion’s strategy of mass arrests has created division and given other environmental movements less space to use direct action around climate justice. “It’s removed even people like me who were used to doing lots of direct action from even feeling safe to that anymore,” she said.

“When I’ve been doing direct action for the last decade, the goal has never been to get arrested. The political realities for people of color … means now if I take direct action they’ve changed… the perception of climate justice activists so that (the) space to engage has been changed, the punishment and the harshness (has worsened).”

On its website, Extinction Rebellion now states: “Our vision for Extinction Rebellion puts love at the heart of change. In this way some people in Extinction Rebellion may choose to express gratitude and love towards police officers. We understand for those that have been victimised by the police that this can be difficult and alienating to witness. We especially ask white people to learn about white privilege.”

Extinction Rebellion ‘is not diverse enough’

As a loosely networked grassroots movement , there is no recognized hierarchy within Extinction Rebellion. But Mawuli Klu – who speaks on behalf of the movement as a leading voice within Extinction Rebellion’s Internationalist Solidarity Network – also admits there is a problem.

“Yes, it’s factual to recognize that XR, from a certain point, is not diverse enough, but there needs to be recognition of the work those of us from non-white communities are now doing within XR,” said Mawuli Klu, whose organization serves the pan-African community. “We would all wish to see more diversity in XR. But it’s important to understand that, like every organization, XR has specific origins.”

“There’s a lot that has to change and fortunately it is changing,” Mawuli Klu adds. “One of the things we’ve been arguing for is for XR to respect the fact that the vast majority of people are not going to do arrestable actions and they need to recognize our historic relationship with the police. XR is listening.

“XR is a mass movement and it takes some time for mass movements to embrace consciousness, but I can assure you the next phases of the rebellion are not going to be exactly like we’ve had in April and October.”

As part of his work with Extinction Rebellion, Mawuli Klu is collaborating with independent internationalist groups based in Ghana and India and is hoping to build a similar network in South America to create “new forms of rebellion … across the world.”

“We have been trying to work to diversify XR, but to do it in a way that responds to the needs of our own communities, particularly communities of the Global South that are here in the UK as diaspora communities,” he explained. Mawuli Klu said that while the Global North has finally woken up to the climate crisis, indigenous communities, people living in the Global South, and the working class have been fighting environmental injustice for years.

In her book “Working-Class Environmentalism,” Karen Bell argues that working-class people have been the most active and courageous environmentalists for centuries.

She says middle-class environmental movements, such as Extinction Rebellion, need to change on many levels.

“We need environmental policies that improve working-class lives – not make them more difficult – if we want to have broad support for sustainability,” she told CNN in an email. “The kinds of policies that would do this are primarily ones that reduce inequality and meet human needs.”

Climate change’s impact on health

Does this mean Extinction Rebellion needs to adapt its message? “They don’t talk about health enough,” Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah told CNN. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah describes herself as an advocate, a London mum who is fighting for clean air and attempting to educate communities about the health impacts of air pollution. It is not her passion, she says, but a matter of life and death.

In 2013, Adoo-Kissi-Debrah’s daughter Ella died aged nine. Ella lived in Lewisham, south London, near the South Circular, a major thoroughfare in the city. For three years leading up to her death, she suffered asthma attacks so severe that they sometimes triggered seizures.

Adoo-Kissi-Debrah wants air pollution to be officially listed as Ella’s cause of death – a first in the UK – replacing the original ruling that Ella died of acute respiratory failure.

“Polar bears, icicles – people in Lewisham can’t relate to that,” Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, who is a Green Party candidate in December’s UK general election, added.

“You talk about the South Circular and the air people are breathing – due to air pollution people are being admitted for asthma attacks, heart attacks, strokes, that’s very real where I come from. We have very different objectives, but it’s all part of a movement.”

Mawuli Klu concedes that Extinction Rebellion “certainly has to improve” its messaging. “It’s not connected into community groups that are doing work on health issues and that is why it’s coming across that health isn’t being talked about enough in Extinction Rebellion,” he said. “There is also a problem with XR’s own publicity. Some of us really do have serious problems with the graphics because they seem to pay a lot of attention to animals, birds, and so on and so forth.”

According to the World Health Organization, nearly 90% of pollution deaths in 2016 occurred in low and middle-income countries, mainly in Asia and Western Pacific regions, and nine in 10 people on the planet lived in places where the WHO air quality guidelines levels were not met. Air pollution estimated to cause 4.2 million premature deaths worldwide in 2016, the report said.

But though dirty air affects almost everyone, it is the least well-off who bear the brunt of the burden, whatever the wealth of their country. There is race inequity, too.

Vivian Huang, deputy director of the Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN), helps organize frontline communities in Richmond, California – home to a massive Chevron oil refinery. In 2015, Chevron paid millions of dollars to the city to settle a lawsuit over a fire at the refinery that sent more than 15,000 people to the hospital with respiratory and other symptoms.

“What Extinction Rebellion is doing is really valuable,” said Huang. “They’ve brought a lot of attention and visibility to the urgency of the climate crisis and they really understand the systemic nature. They bring a lot of creative tactics to really raise the visibility issue.

“At the same time, that’s not everything and that can’t be everything,” she said. “The way to build a broad, powerful movement is to build on the wisdom and expertise that already exists within indigenous and frontline community members.”

Extinction Rebellion has galvanized thousands around the world, but how it responds to internal challenges may define its success in provoking global political action.